Zoo Miami

| Zoo Miami | |

|---|---|

| |

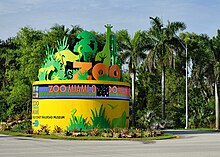

Entrance from State Road 992. | |

| |

| Date opened | 1948 (Crandon Park Zoo) July 4, 1980 (Miami MetroZoo)[1] |

| Location | Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States |

| Land area | 750 acres (304 ha) (324 acres (131 ha) developed)[2] |

| No. of animals | 3,000[2] |

| No. of species | 500[2] |

| Annual visitors | 1+ million[3] |

| Memberships | Association of Zoos and Aquariums |

| Major exhibits | 100[2] |

| Website | www |

The Miami-Dade Zoological Park and Gardens, also known as Zoo Miami, is a zoological park and garden in Miami and is the largest zoo in Florida. Originally established in 1948 at Crandon Park in Key Biscayne, Zoo Miami relocated in 1980 as Miami MetroZoo to the former location of the Naval Air Station Richmond,[4] southwest of Miami in southern unincorporated Miami-Dade County,[5] surrounded by the census-designated places of Three Lakes (north), South Miami Heights (south), Palmetto Estates (east) and Richmond West (west).

The only tropical zoo in the continental United States, Zoo Miami houses over 3,000 animals of around 500 species on almost 750 acres (304 ha), 324 acres (131 ha) of which are developed. It is 4 mi (6 km) around if walked on the path, and features over 100 exhibits.[2] The zoo's communications director is zookeeper Ron Magill.[6] Zoo Miami is accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA).

History

[edit]

The history of Zoo Miami can be traced back to 1948, when a small road show, stranded near Miami, exchanged three monkeys, a goat and two black bears for approximately $270 in repairs for the truck.[7] These six animals were the beginning of the Crandon Park Zoo at Crandon Park on the island of Key Biscayne, just southeast off the coast from downtown Miami.[2] The Crandon Park Zoo occupied 48 acres (19.4 ha) of the park. The first animals in the zoo, including some lions, an elephant and a rhinoceros, had been stranded when a circus went out of business in Miami. Some Galapagos tortoises, monkeys and pheasants were added from the Matheson plantation.[8] By 1967, the Crandon Park Zoo had grown to over 1,200 animals, and was considered one of the top 25 zoos in the country.[9] Other animals were added, including a white Bengal tiger in 1968.

In 1965, Hurricane Betsy devastated the zoo and killed 250 animals. After the hurricane, there was talk of a new zoo for Dade County, but not until December 11, 1970, did Dade County officials apply for 600 acres (243 ha) of land in the Naval Air Station Richmond property. Construction began in 1975. The zoo opened on July 4, 1980,[1] as Miami MetroZoo, with a preview section of 12 exhibits; Asia, the first major exhibit, opened on December 12, 1981. A total of 38 exhibits, covering 200 acres (81 ha), were open to the public at this time.[2]

In the 1980s, the zoo continued to expand. An additional 25 acres (10 ha), with six new African hoofed-mammal exhibits, opened in 1982, along with the zoo's monorail in 1984. After the closing of the 1984 Louisiana World Exposition in New Orleans, the expo’s visitor monorails were moved to Florida to be re-purposed at Miami MetroZoo and operated until 2022.[10][11] Wings of Asia, a 1.6-acre (0.6 ha) free-flight aviary, was opened in December 1984. Three additional African hoofed stock exhibits followed in 1985, and two new exhibits were opened in the African savanna section in 1986. The Australian section of the zoo was opened in 1989, and PAWS, the children's petting zoo, opened in 1989.[2] The Asian Riverlife Experience opened in August 1990.

In 1992, the zoo suffered extensive damage when Hurricane Andrew made landfall in South Florida, on August 24. The small, yet intensely powerful category 5 hurricane toppled over 5,000 trees and destroyed the Wings of Asia aviary (which had been built to withstand winds of up to 120 miles per hour (193 km/h)) resulting in the loss of approximately 100 of the 300 resident birds.[12] Despite the majority of the zoo's animals remaining outside during the duration and aftermath of Hurricane Andrew, only five animals were killed from either debris or the consumption of contaminated water. MetroZoo, though looking dramatically different, reopened on December 18, 1992, with the zoo's tiger temple exhibit renamed in honor of Naomi Browning, a local 12-year-old zoo volunteer who was one of the storm's casualties.

By July 1993, many of the animals that were sent to other zoos and animal parks across the United States (during the zoo's reconstruction) had been returned to Miami, and over 7,000 new trees had been planted to begin restoring the zoo's tree canopy.[13]

In 1994, stray dogs entered the zoo during off-hours, and killed five Thomson's gazelles and two Grant's gazelles.[14]

In 1996, a brush fire burned 100 acres in the southeast portion of the zoo's undeveloped land.[14] Nearly 30 animals from adjacent exhibits were evacuated.[15] The Falcon Batchelor Komodo Dragon Encounter opened that same year, followed by exhibits featuring Andean condors (1999), meerkats (2000), Cuban crocodiles and squirrel monkeys (2001). Dr. Wilde's World, which is an indoor facility for traveling zoological exhibits, was also opened in 2001. The rebuilt Wings of Asia aviary, housing more than 300 individual birds and representing 70 species, refurbished in the spring of 2003.

On July 4, 2010, the zoo was renamed the Miami-Dade Zoological Park and Gardens, or Zoo Miami (for marketing and branding purposes). This was a part of the zoo's 30th anniversary celebration.[1][16] The zoo broke ground on a $43 million project that included an Everglades exhibit and a new state-of-the-art entryway.[17] The Everglades exhibit opened on December 10, 2016.

In 2017, the zoo was struck by Hurricane Irma, which impacted South Florida on September 10. The Amazon and Beyond exhibit suffered the most damage, with widespread tree loss in that area. According to the zoo, one American flamingo, one Great hornbill, and a few other birds died reportedly due to stress.[18] The zoo remained closed until October.[19]

In May 2023, footage of a kiwi named Paora at Zoo Miami being handled by visitors and exposed to daylight caused outrage amongst New Zealanders and conservation experts, including Paora Haitana for whom the bird is named. The New Zealand Department of Conservation stated they would raise their concerns with the AZA.[20][21][22][23] Zoo Miami subsequently apologized and said it would cease these practices.[24]

Conservation efforts

[edit]Zoo Miami supports conservation programs at the local, national and global level, and was a founding member of the AZA's Butterfly Conservation Initiative (BFCI), a program designed to assemble governmental and non-governmental agencies to aid in the population recovery of vulnerable, threatened and endangered butterflies in North America.[citation needed]

The zoo has also provided financial help through the Zoo Miami Conservation Fund to upgrade captive-breeding facilities in Thailand’s zoos, notably for endangered clouded leopards and fishing cats.[25]

Exhibits and animals

[edit]

There are five main exhibit sections in the zoo: Florida: Mission Everglades, Asia, Africa, Amazon and Beyond, and Australia. The zoo's main entry includes an entryway canopy structure, conjoining ticket booths and gift shop, and an adjacent American flamingo exhibit.[17] At the junction of the zoo's main pathways, is the Conservation Action Center, an indoor pavilion featuring interactive exhibits themed to conservation and wildlife preservation. The property includes a large lake, called Lake Iguana. Zoo Miami is characterized by large cage-less, moated exhibits.

From 1984 until 2022, an air-conditioned monorail system traveled around the zoo's premises, providing both an aerial view of the zoo and a convenient way to move between sections.[11] The monorail system had four stations throughout the zoo. Narrated tram rides and guided tours were given daily. The monorail was decommissioned due to unaffordable maintenance costs. There were 5 trains in total, 3 of which were formerly used for the New Orleans World's Fair. One train was decommissioned in 1987 so that it could be used for parts for the others, as the manufacturer ceased business.

Florida: Mission Everglades

[edit]

The Florida: Mission Everglades exhibit features native fauna and flora species found in Florida, particularly from the state's Everglades region.[26] Species displayed include American alligators, American crocodiles, North American river otters, American black bears, Florida panthers, bald eagles, brown pelicans, and roseate spoonbills. The $33 million project features Lostman's River Ride, a gentle airboat ride attraction.

Asia

[edit]The zoo's Asian exhibit features dozens of animals such as Bornean orangutans, Asian elephants, Indian rhinoceros, Sumatran tigers, gaurs, bantengs, lowland anoas, Arabian oryx, Bactrian camels, dromedary camels, Malayan tapirs, sloth bears, dholes, northern white-cheeked gibbons, siamang, as well as a variety of Asian birds. The now-defunct Asian River Life Experience replicated the appearance of an Asian river brook. Until 2023, Zoo Miami was only one of two zoos in the United States to display a pair of black-necked storks.[27] Several species not native to Asia are also found in this area like lions, African painted dogs, spotted hyenas, okapis, addax, sable antelope, addra gazelles, mongoose lemur, black crowned cranes, and Cuban crocodiles.

The American Banker's Family Aviary, Wings of Asia is a walkthrough aviary that's home to approximately 85 species of birds.

Bird Species List:

- Buff-banded rail

- Masked lapwing

- Nicobar pigeon

- Red-knobbed imperial pigeon

- Pied imperial pigeon

- Victoria crowned pigeon

- Mindanao bleeding-heart

- Luzon bleeding-heart

- Crested pigeon

- Pheasant pigeon

- Chestnut-breasted malkoha

- Oriental dollarbird

- Red-vented bulbul

- White-eared bulbul

- Black bulbul

- Black-throated laughingthrush

- White-crested laughingthrush

- Metallic starling

- Black-collared starling

- White-breasted woodswallow

- Black-naped oriole

- White-eared catbird

- Fawn-breasted bowerbird

- Azure-winged magpie

- Javan pond heron

- Painted stork

- White stork

- Straw-necked ibis

- Magpie goose

- Bar-headed goose

- Red-breasted goose

- Spotted whistling duck

- Mandarin duck

- Indian spot-billed duck

- Australian shoveler

- Marbled teal

- Falcated duck

- Tufted duck

- Scaly-sided merganser

- White-winged duck

- Ruddy shelduck

- Great argus

- Germain's peacock-pheasant

- Edward's pheasant

- Green junglefowl

- Green peafowl

- Sarus crane

- Grey-headed swamphen

The zoo's orangutan exhibit once housed Nonja, a female Sumatran orangutan that was relocated from a Dutch zoo to Zoo Miami. She was widely believed to be the oldest living specimen of her species, until her death in 2007.[28] Another notable resident was Carlita, a 21-year-old female white Bengal tiger, who resided in the zoo's tiger enclosure from 1994 until her death in 2013.[29][30]

The Asian exhibit is home to two Asian elephants: an elderly female named Nellie and a young male named Ongard. Dalip (a bull born on June 8, 1966, in Kerela), arrived at the old Crandon Park Zoo on Key Biscayne as a young calf in August 1967, along with his mate Seetna and he is the father to Spike (born on July 2, 1981, in Zoo Miami and he is Dalip's only surviving offspring) who currently lives in the Smithsonian National Zoo in Washington. Seetena and Dalip were separated due to the damage caused by Hurricane Andrew in 1992. Both were separated during the storm, Seetna moved to Two Tails Ranch (Patricia Zerbini) and stayed there for breeding purposes but died of labor issues in 1996 while Dalip returned to Zoo Miami in 1995 where he remained until his death in 2022.[31]

The American Banker's Family Aviary, Wings of Asia is also located here. The aviary features 300 rare birds of 70 species in a temperate mixed forest, and it highlights the evolutionary connection of birds to dinosaurs. At 54,000 square feet (5,017 m2), it is the largest open-air Asian aviary in the Western Hemisphere.[32] The Children's Zoo[33] hosts animals that can be approached to a close distance by guests. Guests can view meerkats, a petting zoo, an exhibit that displays small species of reptiles, amphibians and insects, butterfly gardens, a carousel dedicated to individual animal species, and experience traditional camel rides.

Africa

[edit]

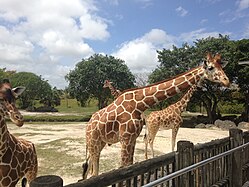

The African loop of the zoo offers animals from different locations on Africa. Visitors can observe species including reticulated giraffes, pygmy hippos, African bush elephants, eastern black rhinoceroses, greater kudus, nyalas, slender-horned gazelles, Grevy's zebras, giant elands, chimpanzees, western lowland gorillas, mountain bongo, yellow-backed duikers, okapis, and servals. Oasis Grill, a small eatery plaza, is situated at the northern end of the African exhibits. Zoo Miami has one of the most diverse collections of hoofed stock in the United States.[34]

Eleven-year-old "Pongo," at sixteen feet the tallest giraffe in the zoo, was euthanized on January 4, 2021, after failing to recover from a foot injury.[35]

Amazon and Beyond

[edit]

Amazon and Beyond, situated in the zoo's northwest corner, opened on December 6, 2008, and is a collection of South America animals. This area has 27 acres (10.9 ha) dedicated to the flora and fauna of South America, and is subdivided into four distinct areas: Village Plaza, Cloud Forest, Amazon Flooded Forest, and Atlantic Forest. Three areas represent native habitats that are found in the Amazonian region—the "cloud forest", the Amazon River basin, and the Atlantic Forest-Pantanal—with species such as giant otters, jaguars, Orinoco crocodiles, giant anteaters, black howler monkeys, black-handed spider monkeys, Hoffmann's two-toed sloths, harpy eagles, fruit bats, poison dart frogs, and various Amazonian fish.[36]

Australia

[edit]

The zoo's Australian habitat showcases specimens from throughout the region of Australia, Oceania, and the Pacific islands, including koalas, southern cassowaries, southern hairy-nosed wombats, cockatiels, and Matschie's tree-kangaroos. Situated near this to habitat, is the 800-seat Sami Family Amphitheater, where daily animal presentations, concerts and cultural events are held.

The amphitheater is named in memory of Albert and Winifred Sami, who anonymously donated an estimated $3 million to the zoo from 1993 until their deaths in 2007 and 2014, respectively.[37] Zoo Miami recently celebrated the birth of a baby koala, who was actually born in May 2019, but only emerged from its mothers pouch on January 8, 2020. The baby koala was named Hope in light of the recent fires that devastated Australia.[38]

Near the Australian habitat is a trail with Galapagos giant tortoises, babirusas, red river hogs, common warthogs, and Visayan warty pigs.

Gallery

[edit]-

African elephant at the zoo

-

American flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber)

-

Orangutan at the zoo

-

Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sondaica)

-

Lar gibbon (Hylobates lar)

-

Black-naped oriole (Oriolus chinensis)

-

Camel

-

Tortoise

-

Rosa 'Miami Moon', one of the many flowering plants at the zoo

-

Giraffe

-

White Tiger

Zoo Miami Foundation

[edit]Zoo Miami Foundation is the 501(c)(3) nonprofit support organization of Zoo Miami. It was founded in 1956 and is responsible for educational programming and capital improvements at the zoo over the years. They are rated as a 4* charity by Charity Navigator (https://www.charitynavigator.org/ein/596192814) and were awarded the Platinum Seal of Transparency by Guidestar (https://www.zoomiami.org/about-zoo-miami-foundation)

See also

[edit]- Gold Coast Railroad Museum (adjacent to Zoo Miami)

- Nonja (Malaysian orangutan)

- Rosie the Elephant

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Renaming of Miami MetroZoo". miamidade.gov. Miami-Dade County. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "About Zoo Miami: Keepin' it wild since 1948". Zoo Miami. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ Castelblanco, Cindy. "Zoo Miami breaks attendance mark, welcomes over 1M guests in 2021". Miami's Community Newspapers. Kendall Gazette.

- ^ Destroyed Richmond Naval Air Station

- ^ "2020 CENSUS – CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Miami-Dade County, FL" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 62 (PDF p. 63/154). Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Hanks, Douglas (April 30, 2015). "The face of Zoo Miami enjoys a star turn in Havana". Miami Herald. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ "Zoo Miami". SOMI Magazine. 12 (4): 15. April–May 2017.

- ^ Blank, Joan Gill. 1996. HIKey Biscayne. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. ISBN 1-56164-096-4. pp. 158–160, 163–164.

- ^ Abraham, Kristin (January 28, 2010). "Visiting Zoo Miami". miamibeachadvisor.com. Miami Beach Advisor. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Cotter, Bill, The 1984 New Orleans World's Fair, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, South Carolina, 2008, p.120. ISBN 0-7385-6856-2

- ^ a b Garcia, Amanda Batchelor, Annaliese (April 1, 2022). "Zoo Miami's monorail takes its final ride". WPLG. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abbady, Tal (1992). "Miami's zoo teems with new life 10 years after Hurricane Andrew". The Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Lohr, Steve (May 21, 2015). "AFTER THE STORMS: THREE REPORTS; Miami". The New York Times. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ a b San Martin, Nancy (March 24, 1996). "Animals Unharmed As Fire Consumes 100 Acres At Zoo". The Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ "Fire Erupts Near Zoo; Animals Evacuated". Los Angeles Times. Times Wire Services. March 24, 1996. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ "Miami MetroZoo Celebrates its 30th Birthday with a New Name". miamimetrozoo.com. Miami Zoo. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Morejon, Liane (May 7, 2014). "Groundbreaking ceremony held at Zoo Miami for Mission Everglades exhibit". Local 10 News. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Herrera, Chabeli (September 13, 2017). "South Florida's attractions suffered severe damage during Irma. But most animals survived". Miami Herald. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ Herrera, Chabeli (September 25, 2017). "Tourism industry to visitors: Don't #prayforMiami. We're fine". Miami Herald. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ Marriner, Chris (May 23, 2023). "Miami Zoo's treatment of Paora the kiwi sparks petition". New Zealand Herald.

- ^ Anderson, Ryan; Dunseath, Finlay (May 23, 2023). "DOC to raise concerns with Miami Zoo over treatment of kiwi". Stuff.

- ^ Ternouth, Louise (May 23, 2023). "Paora Haitana concerned at treatment of namesake kiwi at Miami Zoo". RNZ.

- ^ Wilton, Perry (May 23, 2023). "Conservation specialist slams viral kiwi video at Miami zoo as DoC raises concerns". Newshub.

- ^ Anderson, Ryan (May 24, 2023). "Miami zoo to stop mistreatment of kiwi after concerns raised over welfare". Stuff.

- ^ "Zoo Miami Conservation: Asian Projects". miamimetrozoo.co. Zoo Miami. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ Staletovich, Jenny (December 2, 2016). "Zoo Miami's mission: to make sure the zoo isn't the last place you see these animals". Miami Herald. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Torres, Andrea (August 4, 2023). "Zoo Miami's last black-necked stork dies". local10.com. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- ^ "'World's oldest' orang-utan dies". BBC News. BBC. December 31, 2002. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- ^ Dixon, Lance (September 16, 2014). "Iconic Zoo Miami white tiger euthanized". Miami Herald. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Martin, Vanessa (September 19, 2014). "Carlita Dead: White Bengal Tiger Dies At Zoo Miami". The Huffington Post. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Hanks, Douglas (November 24, 2022). "Dalip, a Miami zoo elephant since the 1960s and one of the nation's oldest, dies at 56". Miami Herald. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Wings of Asia". Zoo Miami. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ "Children's Zoo". Zoo Miami. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ "Zoo Miami". Trip Advisor.

- ^ Teproff, Carli (January 4, 2021). "Pongo was the tallest giraffe at Zoo Miami. A fractured foot has led to a sad goodbye". news.yahoo.com. Miami Herald. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ "Amazon and Beyond Exhibit". Zoo Miami. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ Ron Magill; Dan LeBatard (August 14, 2014). "Zoo Miami's Ron Magill reveals identity of long-anonymous donors of millions". Miami Herald. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ "South Florida zoo celebrates birth of baby koala". FOX 13 News. January 9, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

External links

[edit]- 1948 establishments in Florida

- Aviaries in the United States

- Botanical gardens in Florida

- Buildings and structures in Miami-Dade County, Florida

- Education in Miami-Dade County, Florida

- Parks in Miami-Dade County, Florida

- History of Miami-Dade County, Florida

- Tourist attractions in Miami-Dade County, Florida

- Educational organizations established in 1948

- Zoos established in the 1940s

- Zoos in Florida

- Monorails in the United States